Concrete Japan: buildable statements and the reconstruction of a national identity

Marcela Aragüez

Research Fellow, Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Kenzo Tange, Yamanashi Broadcasting Building, 1966Japan’s need to resurge from the ashes after World War II was an opportunity as much as a challenge. A group of young architects supported by governmental and private initiatives experimented, particularly during the 1960s, with structural systems and construction materials that had been otherwise only conceived in theory in other countries. This way, cities such as Tokyo and Osaka soon became the hub for the design and implementation of innovative urban forms, ranging from the scale of intercity highways to the minimal space of a townhouse. Being concrete the most widely used material during this reconstruction period, Japan remains today as a country filled of solid, brutalist infrastructures in contrast with an inherited tradition of lightweight and temporary architecture.

Kenzo Tange, Yamanashi Broadcasting Building, 1966Japan’s need to resurge from the ashes after World War II was an opportunity as much as a challenge. A group of young architects supported by governmental and private initiatives experimented, particularly during the 1960s, with structural systems and construction materials that had been otherwise only conceived in theory in other countries. This way, cities such as Tokyo and Osaka soon became the hub for the design and implementation of innovative urban forms, ranging from the scale of intercity highways to the minimal space of a townhouse. Being concrete the most widely used material during this reconstruction period, Japan remains today as a country filled of solid, brutalist infrastructures in contrast with an inherited tradition of lightweight and temporary architecture.

This lecture intends to provide an overview of the years in which concrete became the tool for the shaping of a national identity in Japan, and will question the extent to which a certain temporality is nonetheless imprinted in the spaces designed during this period. By using examples of built projects of different scales, from Kenzo Tange’s Yamanashi Broadcasting Building to Takamitsu Azuma’s Tower House, the lecture will show how concrete was used differently according to the building typology, whereby aiming at the common goal of establishing a renovated national style neither attached to Western modernism nor to Japanese tradition.

Swiss brut

Gregorio Astengo

Adjunct Professor, Syracuse Architecture London Program

Otto Glaus, Chur Konvikt, 1967-69Since the introduction of reinforced concrete around the turn of the 19th century, Switzerland has been caught between the economies of growing building industry and the trajectories of a firm national tradition. The seemingly aggressive presence of concrete can be easily seen at odds with Switzerland’s more stereotypical wooden architecture, its natural landscapes and an image of idyllic uniformity which still drive its tourism. However, given its central location and historical permeability, Switzerland was always a hub for structural and formal experimentation, as in the bridges of Robert Maillard, and produced architects, such as Le Corbusier, who became the forefathers of Brutalism itself.

Otto Glaus, Chur Konvikt, 1967-69Since the introduction of reinforced concrete around the turn of the 19th century, Switzerland has been caught between the economies of growing building industry and the trajectories of a firm national tradition. The seemingly aggressive presence of concrete can be easily seen at odds with Switzerland’s more stereotypical wooden architecture, its natural landscapes and an image of idyllic uniformity which still drive its tourism. However, given its central location and historical permeability, Switzerland was always a hub for structural and formal experimentation, as in the bridges of Robert Maillard, and produced architects, such as Le Corbusier, who became the forefathers of Brutalism itself.

Especially since the end of the Second World War, the European crises of Modernist rhetoric generated an array of new interpretations over the significance and position of concrete within a Swiss national discourse. Within this framework, the lecture introduces some of the cultural meanings of ‘cement brut’ in recent and contemporary Switzerland, especially within the country’s notable ideologies of standardisation, commodification and urban development. From Atelier 5 to Peter Zumthor, speaking of ‘Swiss Brutalism’ can still help to unmask the idiosyncratic industries of 20th-century Swiss architecture.

Brutalism Revisited

Owen Hopkins

Senior Curator of Exhibitions and Education, Sir John Soane’s Museum

Brutalismo Caboclo

Davide Sacconi

Director, Syracuse Architecture London Program

Lina Bo Bardi, MASP, 1968The term Brutalism in Brazil identifies the architectures of large spans and rough exposed concrete proposed in São Paulo between 1950 and 1970 by the so-called Escola Paulista. However the definition and the acceptance of this label has been a particularly controversial matter for both architects and historians. In fact, claiming Brutalism in Brazil meant to delve into the contradiction between the international ambitions of a young nation and the poverty of the local means of production, the dreams of a working class revolution and the reality of a feudal organization of society, the dependence from foreign powers and the nurturing of local resources, the rhetoric of the national identity and the actual empowerment of the people. Thus the architectures of the Paulista Brutalism are less bound by an homogeneity of style, materials or construction techniques then by an “anthropophagic” attitude, for which the ethic and aesthetic questions posed by the European Brutalism were swallowed, digested and appropriated from the perspective of the colonised territory. Looking in particular at exemplary works of Vilanova Artigas, Bo Bardi and Arquitetura Nova the paper argues that the historical and contemporary relevance of Brazilian Brutalism is in the attempt to give an emancipatory form to the question of development, that is to say to the fundamental question of the architectural project.

Lina Bo Bardi, MASP, 1968The term Brutalism in Brazil identifies the architectures of large spans and rough exposed concrete proposed in São Paulo between 1950 and 1970 by the so-called Escola Paulista. However the definition and the acceptance of this label has been a particularly controversial matter for both architects and historians. In fact, claiming Brutalism in Brazil meant to delve into the contradiction between the international ambitions of a young nation and the poverty of the local means of production, the dreams of a working class revolution and the reality of a feudal organization of society, the dependence from foreign powers and the nurturing of local resources, the rhetoric of the national identity and the actual empowerment of the people. Thus the architectures of the Paulista Brutalism are less bound by an homogeneity of style, materials or construction techniques then by an “anthropophagic” attitude, for which the ethic and aesthetic questions posed by the European Brutalism were swallowed, digested and appropriated from the perspective of the colonised territory. Looking in particular at exemplary works of Vilanova Artigas, Bo Bardi and Arquitetura Nova the paper argues that the historical and contemporary relevance of Brazilian Brutalism is in the attempt to give an emancipatory form to the question of development, that is to say to the fundamental question of the architectural project.

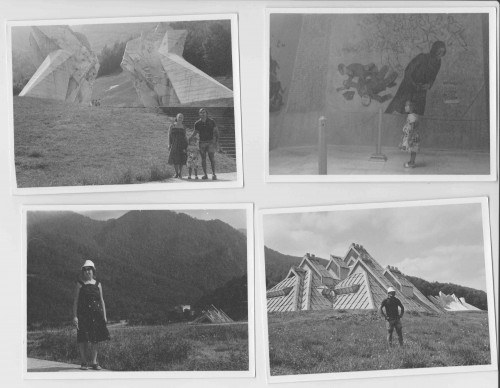

On proper uses of history: ‘Memorability as an Image’ in Yugoslav partisan memorials

Tijana Stevanović

Teaching Fellow, The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Sutjeska Memorial at Tjetište, 1977Yugoslav partisan memorials are nowadays often represented as eerie antiquities of the bygone times, veiled in mystery, worshiped by urban explorers, even speculated upon as works of art by extraterrestrial forces. Abandoned and looted as they stand today, far from partaking Yugoslav socialist revolution, political and social reasons for creating these structures—considered as a particular typology—become increasingly remote from our present ideals, and the world of architecture today struggles to understand the abstractness of their form, notwithstanding awe and admiration. This talk asks: what prevents us today to discuss the creation process of these memorials and its authors’ and commissioners’ original intentions for their purpose?

Sutjeska Memorial at Tjetište, 1977Yugoslav partisan memorials are nowadays often represented as eerie antiquities of the bygone times, veiled in mystery, worshiped by urban explorers, even speculated upon as works of art by extraterrestrial forces. Abandoned and looted as they stand today, far from partaking Yugoslav socialist revolution, political and social reasons for creating these structures—considered as a particular typology—become increasingly remote from our present ideals, and the world of architecture today struggles to understand the abstractness of their form, notwithstanding awe and admiration. This talk asks: what prevents us today to discuss the creation process of these memorials and its authors’ and commissioners’ original intentions for their purpose?

Analysing Peter Reyner Banham’s text ‘The New Brutalism’ published in 1955 in The Architectural Review, and focusing especially on what he identified in this architectural movement as the quality of ‘Memorability as an Image’, this talk suggests that in order to comprehend formal qualities of these extraordinary works of sculptural, landscape, and architectural planning and execution in post-war Yugoslavia we have to be cognizant of their political message at the time when they were regularly visited by general public. The talk revisits Banham’s provocation on ‘proper uses of history’ that he employed to distinguish brutalist—therefore progressive—principles of work in architecture.