Organic

1: Of, relating to, or arising in a bodily organ

2: Of, relating to, or derived from living organisms

3: Of, relating to, yielding, or involving the use of food produced with the use of food produced with the use of feed or fertilizer of plant or animal origin without employment of chemically formulated fertilizers, growth stimulants, antibiotics, or pesticides

4: Forming an integral element of a whole; having systematic coordination of parts

Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Essentially, these four definitions summarize the varied ways in which organic as a term has been described throughout history. Interestingly, the third definition is one that is most ubiquitous in our current society and used as a catch-all word to reference healthier, more conscientious approaches to food production and eating. However, in architectural history, authors like the French architect and theorist Viollet-le-Duc supported the idea of organic in architecture to be a part-to-whole relationship (definition four). Viollet-le-Duc, as had a diverse array of thinkers before him, viewed natural organisms as paradigms of functional and structural expression, and thus of true style.1 This idea was shared by the American architect Louis Sullivan who exemplified this rationale by differentiating the structure from infill - the infill often very ornate and delicate terra-cotta that depicted motifs similar to biological drawings of the time. Another American, Frank Lloyd Wright, still understood organic to mean part-to-whole but was also interested in deriving the latent geometries from living organisms to create architecture. Wright further asserted, "In a fine art sense these designs have grown as natural plants grow."2

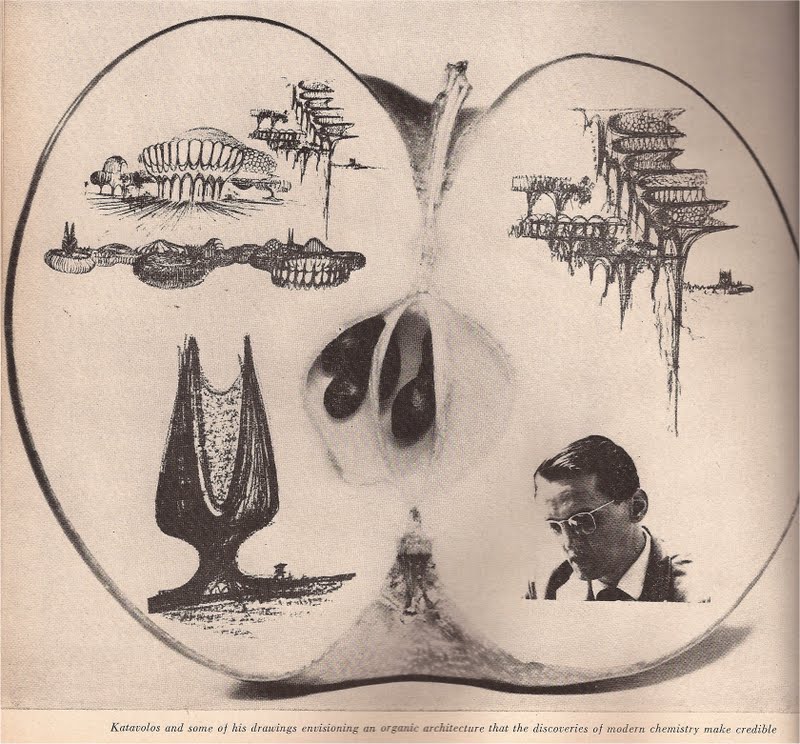

In contemporary discourse, organic in relation to architecture is most often considered 'resembling a living organism in organization or development.' In William Katavalos' essay Organics, this definition can be best portrayed in his thinking of buildings as being grown - developmental verb usage often reserved for living matter. While he uses the word 'organic' he never defines the term but states, "There is a way beyond building just as the principles of waves, parabolas and plummet lines exist beyond the mediums in which they form. So must architecture free itself from traditional patterns and become organic."3

Katavalos continues, "New discoveries in chemistry have led to the production of powdered and liquid materials which when suitably treated with certain activating agents expand to great size and then catalize and become rigid. [...] Accordingly it will be possible to take minute quantities of powder and make them expand into predetermined shapes, such as spheres, tubes, and toruses. [...] "Visualize the new city grow moulded on the sea, of great circles of oil substances producing patterns in which plastics pour to form a network of strips and discs that expand into toruses and spheres, and further perforate for many purposes. "4

The idea of growing architecture or having architecture develop from sub-microscopic levels to expanded built space has changed meaning since Katavalos wrote Organics in 1960. Conceptually, this idea of powder to built-form is already in existence and widely used in process of 3D-printing. Even more recently have been the innovations of 3D-printing organic matter such as bodily organs and even edible meat. The term organic is also about change just as a living organism changes. How we perceive or define the terms organic or organic architecture may be relative to the technologies capable of understanding human life at a particular moment. The current understanding of organic architecture exists somewhere between biomimetic structures and buildings that formally appear to be shaped as a living organism. This definition may change over time as new technologies continue to become closer to achieving what nature itself can achieve.

1 Hoffman, Donald. "Frank Lloyd Wright and Viollet-le-Duc". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 28.3 (Oct 1969): 178.

2 Wright, Frank Lloyd. "In the Cause of Architecture". The Architectural Record XXIII (March 1908): 40

3 Katavalos, William. "Organics". Programs and Manifestoes of 20th-century Architecture. Ed. Ulrich Conrads. Boston: The MIT Press, 1975, 163.

4 Katavalos, William, 163.

Image of William Katavalos and his drawings projected onto an apple. Date Unknown.