Automata

: a mechanism that is relatively self operating

: a machine or control mechanism designed to follow automatically a predetermined sequence of operations or respond to encoded instructions

Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Rooted in the Greek word for automation, which was first used by Homer in the Illiad to describe a self-opening door, the concept of machines operating independent of direct human control has a long history. Mythical automata such as Talos, and artificial man made of bronze, Daedalus' moving statues provide the origins of science-fictions android. More conventionally, mechanical constructions were developed that harnessed potential energy from moving water, wind, or wound springs to provide a simple action or sequence of actions.

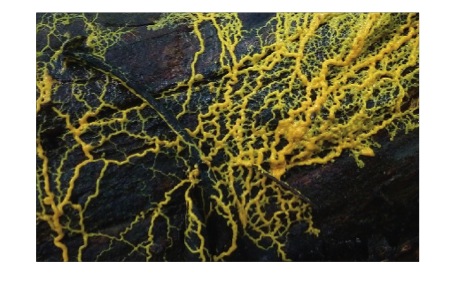

Due to the constraints of available technology up until the present, automata have had to be designed to respond to a limited set of inputs and to provide a likewise limited set of responses to those stimuli. However, advances in computer miniaturization and algorithmic decision making allow for two different streams of exploration to continue. On one hand, there is the potential for automata with greater sensitivity and a broader range of possible responses. On the other hand, research into biological systems like ant colonies and slime molds coupled with nano- and bio-technologies pave the way for the development of microscopic automata that, while limited in their individual abilities, can respond to stimuli and react in aggregate to produce appropriate, complex, results.

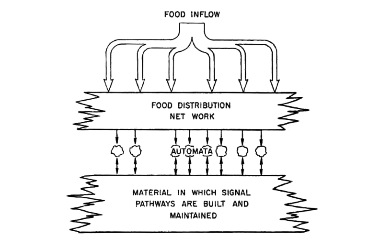

"An automaton, when it appears, sucks in food and builds this food into a communication structure, which structure is subject to degradation and must be maintained." "Clearly in this case, there is a perfectly good sense in which the activity of an automaton... will structure the world around them..." (G. Pask, 1961) p.237,243

In Gordon Pask's 1961 article "A Proposed Evolutionary Model" the potential for automata to evolve over time is explored in depth. Using hypothetical automata composed only of algorithmic computer code Pask attempted to create an environment that would allow for the evolution of the automata over time through competition and 'natural' selection. Beginning with a relatively generic set of automata, Pask provided a constrained 'food' source and set the conditions of the experiment such that automata which successfully collected enough 'food' over the course of a predetermined time were allowed to 'breed' and 'evolve.' Automata which were unable to secure enough 'food' could not pay the cost of survival and thus were eliminated from the gene pool. As iterations of the experiment played out the automata were evolved by compositing the potential actions of two successful automata from the previous iteration. Thus, over time, each automaton was capable of a larger set of singular actions which might improve its ability to fulfill its function, the gathering of resources.

If this model of automaton evolution is combined with an ability to communicate, as seen in slime molds and ant colonies, swarm behavior might develop, allowing for and even more complex behaviors. Were we able to direct such behavior through artificial selection of automata, and create a reward scenario towards the construction of a predetermined end product, automata might be evolved for the express purpose of constructing a real world product to fit the specifications of a Grasshopper computer model.

Model diagram for an automatous system.

(Pask, 1961; p233)

Smile Mold, Physarum polycephalum, exhibits swarm behavior as the individual organisms of which it is composed communicate chemically to direct the behavior of the colony, allowing it to "intelligently" grow towards nutrient sources via optimal pathways in spite of the sharply limited decision making potential of the individual organisms.

Image source: http://animalnewyork.com/

Citations

Margaret Cohen, "Fluid States" in Cabinet, Issue No.16: The Sea (Winter: 2004/2005), pp.75-82.

Keller Easterling, "The Confetti of Empire," in Cabinet, Issue No.16: The Sea (Winter: 2004/2005).

Wolf Hilbertz, "Electrodeposition of Minerals in Sea Water: Experiments and Applications," IEEE Journal on Oceanic Engineering, Vol. OE-4, No.3 (1979), pp.94-113.

Wolf Hilbertz, "Toward CyberTecture," Progressive Architecture (May 1970), pp.98-103.

McHale, John. "The Future of the Future: Inner Space." Architectural Design 37 (February, 1967), pp. 64-95.

Katavolos, William. "Organics," in Ulrich Conrads (Ed.), Programs and Manifestoes on the 20th Century Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970), pp.163-165.

Gordon Pask, "A Proposed Evolutionary Model," H.von Foerster and G.W. Zopf, Jr. (Eds.), Principles of Self Organization: Transactions of the Illinois Symposium, (New York: Harper, 1961), pp: 229-254.